Providing a faster, more reliable internet connection to rural America could be an economic boon. But will tech investments only help the largest, wealthiest farms?

Check out a recent article I’m featured in from Civil Eats, read more here

Providing a faster, more reliable internet connection to rural America could be an economic boon. But will tech investments only help the largest, wealthiest farms?

Check out a recent article I’m featured in from Civil Eats, read more here

Sarah Rotz, Queen’s University, Ontario and Mervyn Horgan, University of Guelph

Article via The Conversation

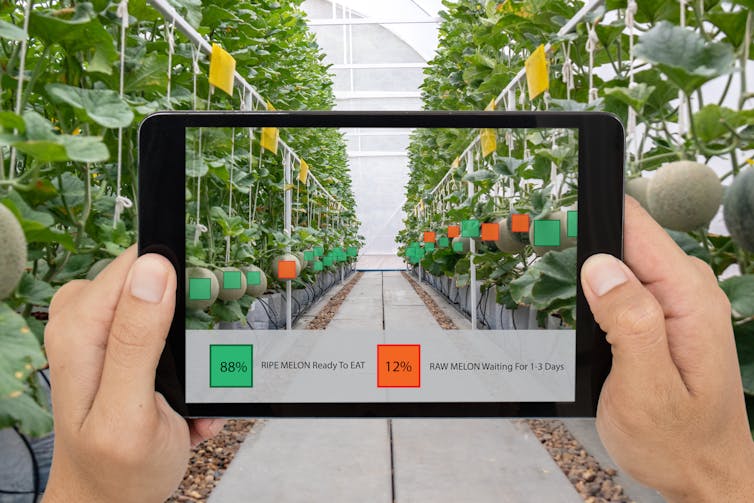

There’s a lot of talk about digital technology and smart cities, but what about smart farms? Many of us still have a romantic view of farmers surveying rolling hills and farm kids cuddling calves, but our food in Canada increasingly comes from industrial-scale factory farms and vast glass and steel forests of greenhouses.

While the social and environmental consequences of agri-food industrialization are fairly well understood, issues around digital technology are now just emerging. Yet, technology is radically transforming farms and farming. And while different in scale and scope, technology is playing a growing role in small and organic farming systems as well.

In reality then, your friendly local farmer will soon spend as much time managing their digital data as they will their dairy herd. The milking apron is being replaced by the milking app.

The Canadian government is investing heavily in climate-smart and precision agricultural technologies (ag-tech). These combine digital tools such as GPS and sensors with automated machines like smart tractors, drones and robots in an attempt to increase farm profits while reducing pesticide and fertilizer use. GPS mapping of crop yields and soil characteristics help to cut costs and increase profits, so while seeds still grow in soil, satellites are increasingly part of the story. There’s no doubt that ag-tech may be promising for governments, investors and corporations, but the benefits are far less clear for farm owners and workers.

There is little research on the potential social impacts of ag-tech specifically, so a group of researchers at the University of Guelph conducted a study to figure out some of the likely impacts of the technological revolution in agriculture.

While changes in agriculture show promise for increasing productivity and profits and reducing pesticides and pollution, the future of farming is not all rosy.

Corporate control of many agricultural inputs — seeds, feed, fertilizers, machinery — is well documented. Agricultural land is also increasing in cost and farms are getting bigger and bigger. It is likely that digital agriculture will exacerbate these trends. We’re especially interested in what farm work will look like as the digital revolution unfolds.

While rising costs are always a concern for producers and consumers, we have two main concerns about how the digital revolution is changing farm work in particular.

First, who owns all of the data being produced in precision agriculture? Farm owners and workers produce data that has massive potential for commercial exploitation. However, just who gets to harvest the fruits of this digital data labour is unclear.

Should it flow to those who produce it? Should it be something that we own collectively? Unfortunately, if smart farms are anything like smart cities, then it looks like corporate control of data could tighten.

Second, it’s very likely that ag-tech will lead to an even more sharply divided labour force. So-called “high-skilled” managers trained in data management and analysis will oversee operations, while many ostensibly “lower-skilled” jobs are replaced. Remaining on-the-ground labourers will find themselves in working conditions that are increasingly automated, surveilled and constrained. For instance, in fruit and vegetable greenhouses inputs are increasingly being controlled remotely, but migrant workers still do much of the planting and harvesting by hand. And, they do so under conditions of severe physical and social immobility.

There is a wealth of research documenting the vulnerable position of migrant agricultural workers from coast to coast in Canada and elsewhere.

If we don’t direct it in a humane way, the digital revolution in agriculture is likely to heighten these vulnerabilities.

Our food system is built on centuries of Indigenous land theft, dislocation and the suppression of Indigenous foodways while relying heavily on exploitable (Indigenous, migrant and racialized) labour. Across North America, farm workers have long been excluded from basic labour laws, legal status and the right to unionize.

And now, increased productivity often relies on increased exploitation – just ask anyone working in a FoxConn factory. As a result, our current food system is rife with exploitative practices, from production through to distribution, with racialized immigrants bearing the brunt.

Meanwhile, there is evidence that automation tends to negatively impact already marginalized workers.

The digital revolution in agriculture has a double edge. Smart farms bring promise, but automation in agricultural production and distribution will eliminate many jobs.

Our concern is that the suite of jobs that remain will only deepen economic inequities — with more privileged university graduates receiving the bulk of the well-paid work, while further stripping physical labourers of their power and dignity.

There is no magic pill, but our governments do have options. Policy and legislation can shift the path of ag-tech to better support vulnerable farm workers and populations. In doing so, the looming issue of land ownership and repatriation must be addressed in Canada, with Indigenous nations at the head of the table alongside marginalized workers and farmers. Supporting pathways to farming and permanent residency for migrant workers, as well as training for digital skill-building can help to close more immediate gaps.

We need to ready ourselves for how radical transformations in food production and distribution will impact land prices, property rights and working conditions. Our folksy view of farming is due for an update.

Sarah Rotz, Postdoctoral Fellow , Queen’s University, Ontario and Mervyn Horgan, Visiting Fellow, Department of Sociology, Yale University and Associate Professor of Sociology, University of Guelph

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

New technologies in agriculture are collecting massive amounts of agricultural data. Drones, robots, sensors, and satellites are generating more data than farmers know what to do with. Take for example, Climate Pro sensors, which are said to generate up to 7 gigabytes of data per acre, and with the average farm size in Canada being 820 acres – that’s a lot of data! While these technologies have been hyped to increase sustainability and productivity, a key question still remains: how does all this data get turned into information – and – information for who?

Farmers are still learning how to use this data to make decisions to improve their farms. When I interviewed farmers for my Master’s thesis, many of those using these technologies had taught themselves how to interpret the data. Others were beginning to make use of a new line of services being offered by a growing number of agricultural companies providing data management assistance.

While we are starting to understand the impacts of data and new technologies on the farm, there are still a lot of questions about what happens to the data once it leaves the farm. Companies have a lot to gain by collecting this data, and according to many data sharing agreements, farmers don’t necessarily own the data that their technologies are generating. According to one report by the American Farm Bureau, 82% of farmers said that they had no idea what companies were doing with their data. Additionally, some companies are even starting to pay farmers for their data, such as Farmobile, who sells their sensor technologies to farmers, the sensors collect information such as harvest data, and then Farmobile finds buyers for this data and pays the farmer. Who is buying this data though? Are other companies selling these types of technologies also selling farmer data but not paying farmers for it?

Most of us are well aware that social media companies, like Facebook, share information to third parties in order to make overwhelming profits through targeted advertising. Yet, in the agricultural industry with the collection of all types of new data, are farmers facing the same type of exploitation?

The farmers that I spoke with were a bit divided over what the outcomes of all this big data collection would be for the industry – some were hopeful that it would lead to new innovations that could benefit their farm, while skeptics believed that this data would lead to new regulations and monitoring. Some organizations have attempted to create more transparency in agricultural data governance, such as Ag Data Transparent, which is a third-party that provides a certification to companies who are practicing best management principles for handling farm data. The Ag Data Coalition is another non-profit organization that is working to create a neutral place for farmers to store and share their data in an attempt to give farmers more control over their data.

Still the black-box of how agricultural data moves from the farm through the agricultural supply chain remains, as large processors (such as Mondelez International) are increasingly starting to require the type of data that is generated by precision agriculture technologies in order to make sustainability claims. As these new technologies continue to be adopted by farmers worldwide, the agricultural industry is in need of effective policy around data management.

We’re currently seeing a massive shift toward automation and digitalization in systems and institutions across the world. Many scholars and activists have written about the ethical dimensions and potential pitfalls of big data (Zwitter 2014; Illiadis and Russo 2016), including issues around surveillance (Lyon 2014), access and inequity (Lanier, 2014; Felt 2016; Kitchin 2014). There has also been a growing field of work exploring how digitalisation will exacerbate power inequities in the food system (Bronson and Knezevic 2016; Carolan 2016a, 2018, 2016b; Mooney 2018) And finally, important research is happening around issues of labour injustice and inequity in food and agriculture (Basok, 2002; Horgan and Liinamaa, 2017; Walia, 2010; Robillard et al., 2018; Reid-Musson, 2017; Weiler, et. al. 2017)

Within this context, a group of us got together to explore some key trends being observed at the nexus of agricultural production, technology, and labour in North America, with a particular focus on Canada. After reflecting on our discussions, reading the literature, and analysing the data, we wrote a paper that highlights three key tensions we’ve observed: 1) the complex relationship between rising land costs and automation; 2) the development of a high-skill/low-skilled bifurcated labour market; and 3) growing issues around the control of digital data itself. In the paper we apply a social justice lens to consider the potential impacts of digital agricultural technologies for farm labour and rural communities, which directs our attention to racial exploitation in agricultural labour specifically. After all, structures of racism, classism and patriarchy have long underpinned Canadian agriculture (Carter, 1990; Holtslander, 2015; Laliberte and Satzewich, 2008; Perry, 2012; Preibisch, 2007). After exploring these tensions over the past year, it seems that policy and research must work to shift the trajectory of digitalization in ways that support food production as well as marginalized agricultural labourers. We also point to some key areas for future research—which is lacking to date. We emphasize that the current enthusiasm for digital agriculture should not blind us to the specific ways that new technologies intensify exploitation and deepen both labour and spatial marginalization

You can read the full paper here (open access):

Another group of us have also just published a similar paper that reviews the political economy of big data and agriculture more generally, which can be found here: The Politics of Digital Agricultural Technologies: A Preliminary Review

Looking forward to hearing your feedback!

A recent episode of Food Talk with guest James Collins of DowDuPont and Corteva Agriscience got me thinking: how is big ag responding to political shifts in food production?

As host Dani Nierenberg and Collins discussed the ins and outs of ag-tech, I noticed that companies are very much taking cues from grassroots producer and consumer movements about what ‘responsible’ and ‘sustainable’ agriculture ought to look like. By that I mean the PR of private agribusiness.

Discursively, ag companies are pretty self-aware of their current image. After all, we need to look no further than the consecutive PR disasters at Monsanto to see what political ignorance can mean for even the largest companies: Monsanto’s name has been ditched in the wake of its sale to Bayer. Why? Well, perhaps it’s because Monsanto is simply too tarnished to remain relevant in an increasingly contentious and economically competitive agri-food landscape.

What, it seems, we are seeing is an emerging set of strategies in the longer-standing privatization of agricultural extension. Companies seem increasingly concerned with ‘community-based’ partnerships and ‘inclusive agriculture’ as a model of working at the production end of the food system. Companies like Bayer and DowDuPont seem to be paying close attention to agri-business resistance movements and are adopting a disturbingly similar rhetoric of community and grassroots partnerships that prioritize ‘accountability’, presenting themselves as a real ‘business with a conscience’. A quick look at Corteva Agriscience’s website—a division of DowDuPont that deals specifically with production agriculture extension and services from seed technologies and chemical crop inputs to digital farm management software—illustrates this well. After all, Corteva’s primary mission is to bring production agriculture to farmers across the world. How are they hoping to achieve this? One word: community.

As Collins described the work of Corteva the strategy became fairly clear: the more they can embed their people and products into farming communities, the deeper and longer the relationships will be. And in an era of dwindling public extension services in both North America and Europe, farmers are looking for reliable advisors and mentors that are willing to ‘come to them’ so to speak. After all, this isn’t really a thing that government agencies are doing anymore. In Ontario for instance extension services have diminished dramatically since the 80’s, and farmers aren’t happy about it. In my PhD research with farmers across Ontario, I repeatedly heard feelings of frustration and fear over being ‘ignored’ and ‘left behind’ by government as the Ontario Ministry has increasingly re-positioned itself away from extension and toward policy, research and innovation. In this context, it’s perhaps unsurprising that, as these companies grow and merge, subsidiaries will surface to fill this gap, similar to strategies that companies like Cargill took in creating spin offs like Black River to handle private agri-food equity in the global south. Under this structure, I wonder whether many farmers are even aware that these subsidiaries—now hyper-focused on building community-based partnerships, are in fact affiliated with some of the largest agri-food giants in the world.

More to the point though, how effective might this strategy be for enlisting farmers who are currently using non-industrial methods into industrial models? And in turn, how might food movements respond to and resist these shifts?